Diarrhea Overview

Diarrhea (from the Greek, διὰρροια meaning “a flowing through”[2]), also spelled diarrhoea, is the condition of having three or more loose or liquid bowel movements per day.[3]

Diarrhea is a common cause of death in developing countries and the second most common cause of infant deaths worldwide. The loss of fluids through diarrhea can cause dehydration and electrolyte imbalances. In 2009 diarrhea was estimated to have caused 1.1 million deaths in people aged 5 and over[4] and 1.5 million deaths in children under the age of 5.[1] Oral rehydration salts and zinc tablets are the treatment of choice and have been estimated to have saved 50 million children in the past 25 years.[1]

Definition

Diarrhea is defined by the World Health Organization as having 3 or more loose or liquid stools per day or as having more stools than is normal for that person.[3]

Secretory

Secretory diarrhea means that there is an increase in the active secretion, or there is an inhibition of absorption. There is little to no structural damage. The most common cause of this type of diarrhea is a cholera toxin that stimulates the secretion of anions, especially chloride ions. Therefore, to maintain a charge balance in the lumen, sodium is carried with it, along with water. In this type of diarrhea intestinal fluid secretion is isotonic with plasma even during fasting .[5]

Osmotic

Osmotic diarrhea occurs when too much water is drawn into the bowels. This can be the result of maldigestion (e.g., pancreatic disease or Coeliac disease), in which the nutrients are left in the lumen to pull in water. Osmotic diarrhea can also be caused by osmotic laxatives (which work to alleviate constipation by drawing water into the bowels). In healthy individuals, too much magnesium or vitamin C or undigested lactose can produce osmotic diarrhea and distention of the bowel. A person who has lactose intolerance can have difficulty absorbing lactose after an extraordinarily high intake of dairy products. In persons who have fructose malabsorption, excess fructose intake can also cause diarrhea. High-fructose foods that also have a high glucose content are more absorbable and less likely to cause diarrhea. Sugar alcohols such as sorbitol (often found in sugar-free foods) are difficult for the body to absorb and, in large amounts, may lead to osmotic diarrhea.[5]

Exudative

Exudative diarrhea occurs with the presence of blood and pus in the stool. This occurs with inflammatory bowel diseases, such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, and other severe infections.[5]

Motility-related

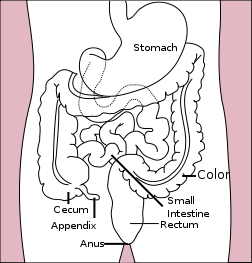

Motility-related diarrhea is caused by the rapid movement of food through the intestines (hypermotility). If the food moves too quickly through the GI tract, there is not enough time for sufficient nutrients and water to be absorbed. This can be due to a vagotomy or diabetic neuropathy, or a complication of menstruation[citation needed]. Hyperthyroidism can produce hypermotility and lead to pseudodiarrhea and occasionally real diarrhea. Diarrhea can be treated with antimotility agents (such as loperamide). Hypermotility can be observed in patients who have had portions of their bowel removed, allowing less total time for absorption of nutrients.

Inflammatory

Inflammatory diarrhea occurs when there is damage to the mucosal lining or brush border, which leads to a passive loss of protein-rich fluids, and a decreased ability to absorb these lost fluids. Features of all three of the other types of diarrhea can be found in this type of diarrhea. It can be caused by bacterial infections, viral infections, parasitic infections, or autoimmune problems such as inflammatory bowel diseases. It can also be caused by tuberculosis, colon cancer, and enteritis.

Dysentery

Generally, if there is blood visible in the stools, it is not diarrhea, but dysentery. The blood is trace of an invasion of bowel tissue. Dysentery is a symptom of, among others, Shigella, Entamoeba histolytica, and Salmonella.

Differential diagnosis

Diarrhea is most commonly due to viral gastroenteritis with rotavirus accounting for 40% of cases in children under five.[1](p. 17) In travelers however bacterial infections predominate.[6]

It can also be the part of the presentations of a number of medical conditions such as: Crohn’s disease or mushroom poisoning.

Infections

There are many causes of infectious diarrhea, which include viruses, bacteria and parasites.[7] Norovirus is the most common cause of viral diarrhea in adults,[8] but rotavirus is the most common cause in children under five years old.[9] Adenovirus types 40 and 41,[10] and astroviruses cause a significant number of infections.[11]

The bacterium campylobacter is a common cause of bacterial diarrhea, but infections by salmonellae, shigellae and some strains of Escherichia coli (E.coli) are frequent.[12] In the elderly, particularly those who have been treated with antibiotics for unrelated infections, a toxin produced by Clostridium difficile often causes severe diarrhea.[13]

Parasites do not often cause diarrhea except for the protozoan Giardia, which can cause chronic infections if these are not diagnosed and treated with drugs such as metronidazole,[14] and Entamoeba histolytica.[15][16]

Other infectious agents such as parasites and bacterial toxins also occur.[17] In sanitary living conditions where there is ample food and a supply of clean water, an otherwise healthy person usually recovers from viral infections in a few days. However, for ill or malnourished individuals, diarrhea can lead to severe dehydration and can become life-threatening.[18]

Malabsorption

Malabsorption is the inability to absorb food, mostly in the small bowel but also due to the pancreas.

Causes include celiac disease (intolerance to wheat, rye, and barley gluten, the protein of the grain), lactose intolerance (intolerance to milk sugar, common in non-Europeans), fructose malabsorption, pernicious anemia (impaired bowel function due to the inability to absorb vitamin B12), loss of pancreatic secretions (may be due to cystic fibrosis or pancreatitis), short bowel syndrome (surgically removed bowel), radiation fibrosis (usually following cancer treatment), and other drugs, including agents used in chemotherapy.

Inflammatory bowel disease

The two overlapping types here are of unknown origin:

- Ulcerative colitis is marked by chronic bloody diarrhea and inflammation mostly affects the distal colon near the rectum.

- Crohn’s disease typically affects fairly well demarcated segments of bowel in the colon and often affects the end of the small bowel.

Irritable bowel syndrome

Another possible cause of diarrhea is irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) which usually presents with abdominal discomfort relieved by defecation and unusual stool (diarrhea or constipation) for at least 3 days a week over the previous 3 months.[19] There is no direct treatment for IBS, however symptoms can be managed through a combination of dietary changes, soluble fiber supplements, and/or medications.

Other causes

- Diarrhea can be caused by chronic ethanol ingestion.[20]

- Ischemic bowel disease. This usually affects older people and can be due to blocked arteries.

- Hormone-secreting tumors: some hormones (e.g., serotonin) can cause diarrhea if excreted in excess (usually from a tumor).

- Chronic mild diarrhea in infants and toddlers may occur with no obvious cause and with no other ill effects; this condition is called toddler’s diarrhea.

Pathophysiology

Evolution

According to two researchers, Nesse and Williams, diarrhea may function as an evolved expulsion defense mechanism. As a result, if it is stopped, there might be a delay in recovery.[21] They cite in support of this argument research published in 1973 which found that treating Shigella with the anti-diarrhea drug (Lomotil) caused people to stay feverish twice as long as those not so treated. The researchers indeed themselves observed that: “Lomotil may be contraindicated in shigellosis. Diarrhea may represent a defense mechanism”.[22]

Diagnostic approach

The following types of diarrhea may indicate further investigation is needed:

- In infants

- Moderate or severe diarrhea in young children

- Associated with blood

- Continues for more than two days

- Associated non-cramping abdominal pain, fever, weight loss, etc

- In travelers

- In food handlers, because of the potential to infect others;

- In institutions such as hospitals, child care centers, or geriatric and convalescent homes.

A severity score is used to aid diagnosis in children.[23]

Prevention

A rotavirus vaccine has the potential to decrease rates of diarrhea.[1]

Management

In many cases of diarrhea, replacing lost fluid and salts is the only treatment needed. This is usually by mouth – oral rehydration therapy – or, in severe cases, intravenously.[1] Diet restrictions such as the BRAT diet are no longer recommended.[24] Research does not support the limiting of milk to children as doing so has no effect on duration of diarrhea.[25]

Medications such as loperamide (Imodium), bismuth subsalicylate may be beneficial, however they may be contraindicated in certain situations.[26]

Medications

- Antibiotics – While antibiotics are beneficial in certain type of acute diarrhea they are usually not used except in specific situations.[27][28] There are concerns that antibiotic may increase the risk of hemolytic uremic syndrome in people infected with Escherichia coli O157:H7.[29] In resource poor countries treatment with antibiotics may be beneficial.[28]

- Anti motility agents – Anti motility agents like loperamide are effective at reducing the duration of diarrhea.[28]

- Bismuth compounds – While bismuth compounds (Pepto-Bismol) decreased the number of bowel movements in those with travelers’ diarrhea it does not decrease the length of illness.[30] These agents should only be used if bloody diarrhea is not present.[31]

Alternative therapies

Probiotics are bacterial supplements that can help prevent recurrence of diarrhea. The most widely used probiotics include lactobacillus and saccharomyces boulardii. For those who suffer from lactose intolerance, taking digestive enzymes containing lactase when consuming dairy products is recommended.

Epidemiology

World wide in 2004 approximately 2.5 billion cases of diarrhea occurred which results in 1.5 million deaths among children under the age of five.[1] Greater than half of these were in Africa and South Asia.[1] This is down from a death rate of 5 million per year two decades ago.[1] Diarrhea remains the second leading cause of death (16%) after pneumonia (17%) in this age group.[1]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j “whqlibdoc.who.int” (pdf). World Health Organization. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241598415_eng.pdf.

- ^ medterms dictionary. “Definition of Diarrhea”. Medterms.com. http://www.medterms.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=2985.

- ^ a b “Diarrhoea”. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/topics/diarrhoea/en/.

- ^ Straits Times:Diarrhoea kills 3 times more

- ^ a b c http://www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/digestive-diseases-diarrhea

- ^ Wilson ME (December 2005). “Diarrhea in nontravelers: risk and etiology”. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41 Suppl 8: S541–6. doi:10.1086/432949. PMID 16267716.

- ^ Navaneethan U, Giannella RA (November 2008). “Mechanisms of infectious diarrhea”. Nature Clinical Practice. Gastroenterology & Hepatology 5 (11): 637–47. doi:10.1038/ncpgasthep1264. PMID 18813221.

- ^ Patel MM, Hall AJ, Vinjé J, Parashar UD (January 2009). “Noroviruses: a comprehensive review”. Journal of Clinical Virology : the Official Publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology 44 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2008.10.009. PMID 19084472.

- ^ Greenberg HB, Estes MK (May 2009). “Rotaviruses: from pathogenesis to vaccination”. Gastroenterology 136 (6): 1939–51. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.076. PMID 19457420.

- ^ Uhnoo I, Svensson L, Wadell G (September 1990). “Enteric adenoviruses”. Baillière’s Clinical Gastroenterology 4 (3): 627–42. doi:10.1016/0950-3528(90)90053-J. PMID 1962727.

- ^ Mitchell DK (November 2002). “Astrovirus gastroenteritis”. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 21 (11): 1067–9. doi:10.1097/01.inf.0000036683.11146.c7 (inactive 2009-12-18). PMID 12442031.

- ^ Viswanathan VK, Hodges K, Hecht G (February 2009). “Enteric infection meets intestinal function: how bacterial pathogens cause diarrhoea”. Nature Reviews. Microbiology 7 (2): 110–9. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2053. PMID 19116615.

- ^ Rupnik M, Wilcox MH, Gerding DN (July 2009). “Clostridium difficile infection: new developments in epidemiology and pathogenesis”. Nature Reviews. Microbiology 7 (7): 526–36. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2164. PMID 19528959.

- ^ Kiser JD, Paulson CP, Brown C (April 2008). “Clinical inquiries. What’s the most effective treatment for giardiasis?”. The Journal of Family Practice 57 (4): 270–2. PMID 18394362. http://www.jfponline.com/Pages.asp?AID=6066. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ Dans L, Martínez E (June 2006). “Amoebic dysentery”. Clinical Evidence (15): 1007–13. PMID 16973041.

- ^ Gonzales ML, Dans LF, Martinez EG (2009). “Antiamoebic drugs for treating amoebic colitis”. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online) (2): CD006085. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006085.pub2. PMID 19370624.

- ^ Wilson ME (December 2005). “Diarrhea in nontravelers: risk and etiology”. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41 Suppl 8: S541–6. doi:10.1086/432949. PMID 16267716.

- ^ Alam NH, Ashraf H (2003). “Treatment of infectious diarrhea in children”. Paediatr Drugs 5 (3): 151–65. PMID 12608880.

- ^ Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC (2006). “Functional bowel disorders”. Gastroenterology 130 (5): 1480–91. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. PMID 16678561.

- ^ Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005. ISBN 0-07-139140-1.

- ^ Williams, George; Nesse, Randolph M. (1996). Why we get sick: the new science of Darwinian medicine. New York: Vintage Books. pp. 36–38. ISBN 0-679-74674-9.

- ^ DuPont HL, Hornick RB (December 1973). “Adverse effect of lomotil therapy in shigellosis”. JAMA 226 (13): 1525–8. doi:10.1001/jama.226.13.1525. PMID 4587313.

- ^ Ruuska T, Vesikari T (1990). “Rotavirus disease in Finnish children: use of numerical scores for clinical severity of diarrhoeal episodes”. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 22 (3): 259–67. doi:10.3109/00365549009027046. PMID 2371542.

- ^ King CK, Glass R, Bresee JS, Duggan C (November 2003). “Managing acute gastroenteritis among children: oral rehydration, maintenance, and nutritional therapy”. MMWR Recomm Rep 52 (RR-16): 1–16. PMID 14627948. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5216a1.htm.

- ^ “BestBets: Does Withholding milk feeds reduce the duration of diarrhoea in children with acute gastroenteritis?”. http://www.bestbets.org/bets/bet.php?id=1728.

- ^ Schiller LR (2007). “Management of diarrhea in clinical practice: strategies for primary care physicians”. Rev Gastroenterol Disord 7 Suppl 3: S27–38. PMID 18192963.

- ^ Dryden MS, Gabb RJ, Wright SK (June 1996). “Empirical treatment of severe acute community-acquired gastroenteritis with ciprofloxacin”. Clin. Infect. Dis. 22 (6): 1019–25. PMID 8783703.

- ^ a b c de Bruyn G (2008). “Diarrhoea in adults (acute)”. Clin Evid (Online) 2008. PMID 19450323.

- ^ Wong CS, Jelacic S, Habeeb RL, Watkins SL, Tarr PI (June 2000). “The risk of the hemolytic-uremic syndrome after antibiotic treatment of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections”. N. Engl. J. Med. 342 (26): 1930–6. doi:10.1056/NEJM200006293422601. PMID 10874060.

- ^ DuPont HL, Ericsson CD, Farthing MJ, et al. (2009). “Expert review of the evidence base for self-therapy of travelers’ diarrhea”. J Travel Med 16 (3): 161–71. doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2009.00300.x. PMID 19538576.

- ^ Pawlowski SW, Warren CA, Guerrant R (May 2009). “Diagnosis and treatment of acute or persistent diarrhea”. Gastroenterology 136 (6): 1874–86. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.072. PMID 19457416.

- ^ “Mortality and Burden of Disease Estimates for WHO Member States in 2004” (xls). World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/entity/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/gbddeathdalycountryestimates2004.xls.

Source: Wikipedia – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diarrhea